In 2008, following the sale of a family home, a modest piece of land near the Sariska forest boundary was acquired at the insistence of Mr. Shekhawat’s wife. There were no tigers then. The land was rocky, depleted, and largely abandoned-once used to sort stone from the Bhagani copper mines, which supplied British India during the colonial era. Only four invasive trees remained. But the land offered sweeping views of the Aravallis and sat close to a historic Shiva temple. It felt quietly powerful. There was no intention to build a lodge.

The first years were spent trying to heal the land. Initial rewilding efforts were challenging, 20,000 saplings planted, many lost to poor soil, extreme temperatures, and erosion. The approach shifted. Native grasses were introduced to restore soil health. Water-retention ponds were created to recharge the ground. Mulch and organic matter slowly returned microbial life to the soil.

After two monsoons, the land began to change. With plants came insects. With insects came birds. In 2024, velvet bugs, rare indicators of chemical-free ecosystems appeared for the first time. What had once been rubble had become grassland forest.

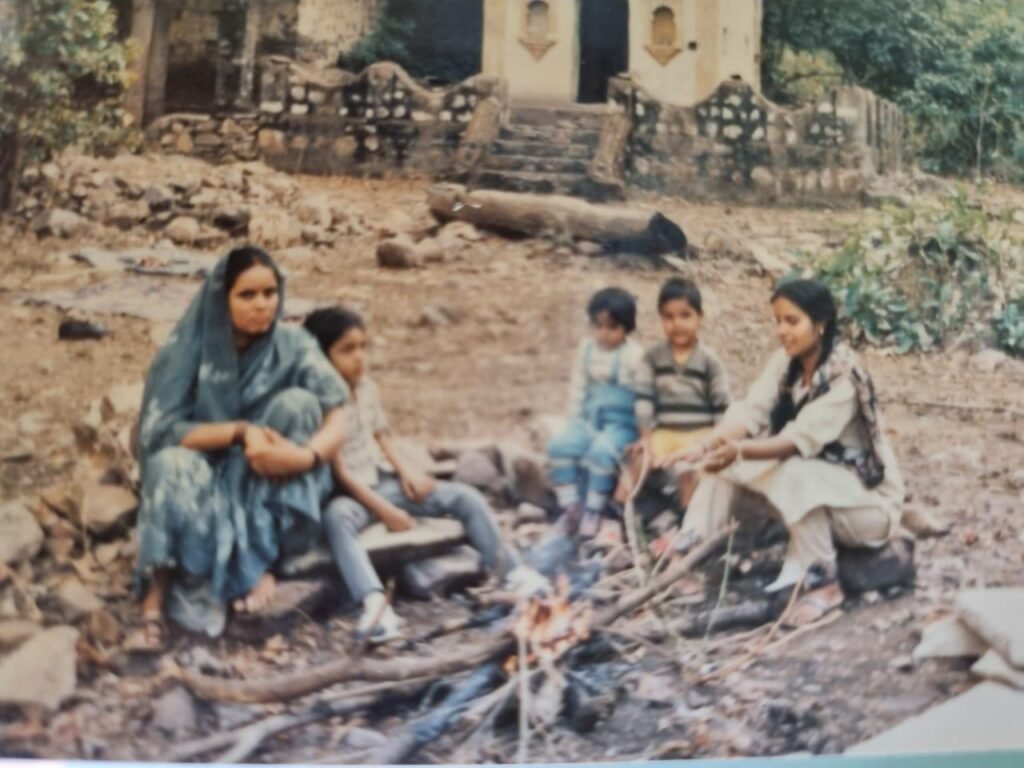

The local community was involved from the very beginning. People joined plantation efforts, construction, and later operations. Local stone, reclaimed wood, and materials salvaged from old havelis shaped the architecture. Artisans-masons, carpenters, glassblowers, brass sculptors, dhurrie weavers, and textile workers from Kutch worked alongside local tailors to craft interiors rooted in place. Women trained in gardens, housekeeping, and laundry; men in kitchens, service, and driving, skills shared, not outsourced.

In 2021, the idea of a lodge finally took shape. Not as a resort, but as a low-impact wilderness stay with limited rooms, where experiences, history, culture, wildlife, and landscape remained central.

Built across 15 acres, only 20 percent of the land was developed. The rest was left to forest and grassland. Architecture stayed low. Materials were reused. The lodge was designed to sit within the land, not above it.